An Introduction To: The Rhône Valley

· Peter Mitchell MW Peter Mitchell MW on

Jeroboams Education is a new series on our blog providing you with the lowdown on the most iconic wine producing regions of the world. Led by our super buying team, Peter Mitchell MW and Maggie MacPherson will introduce you to the key facts and a little history of all the regions you recognise but perhaps don’t know too well. To help really further your education, why not drink along? Browse our Rhône selection.

Introduction

The Rhône is primarily a red wine area (though less than it used to be) and regularly offers some of the best value fine wine in the world, along with vast amounts of cheap easy drinking. Sales in the UK have never reflected the quality and value here, despite many of the wines offering powerful fruit and a generosity wholly in tune with modern consumer tastes.

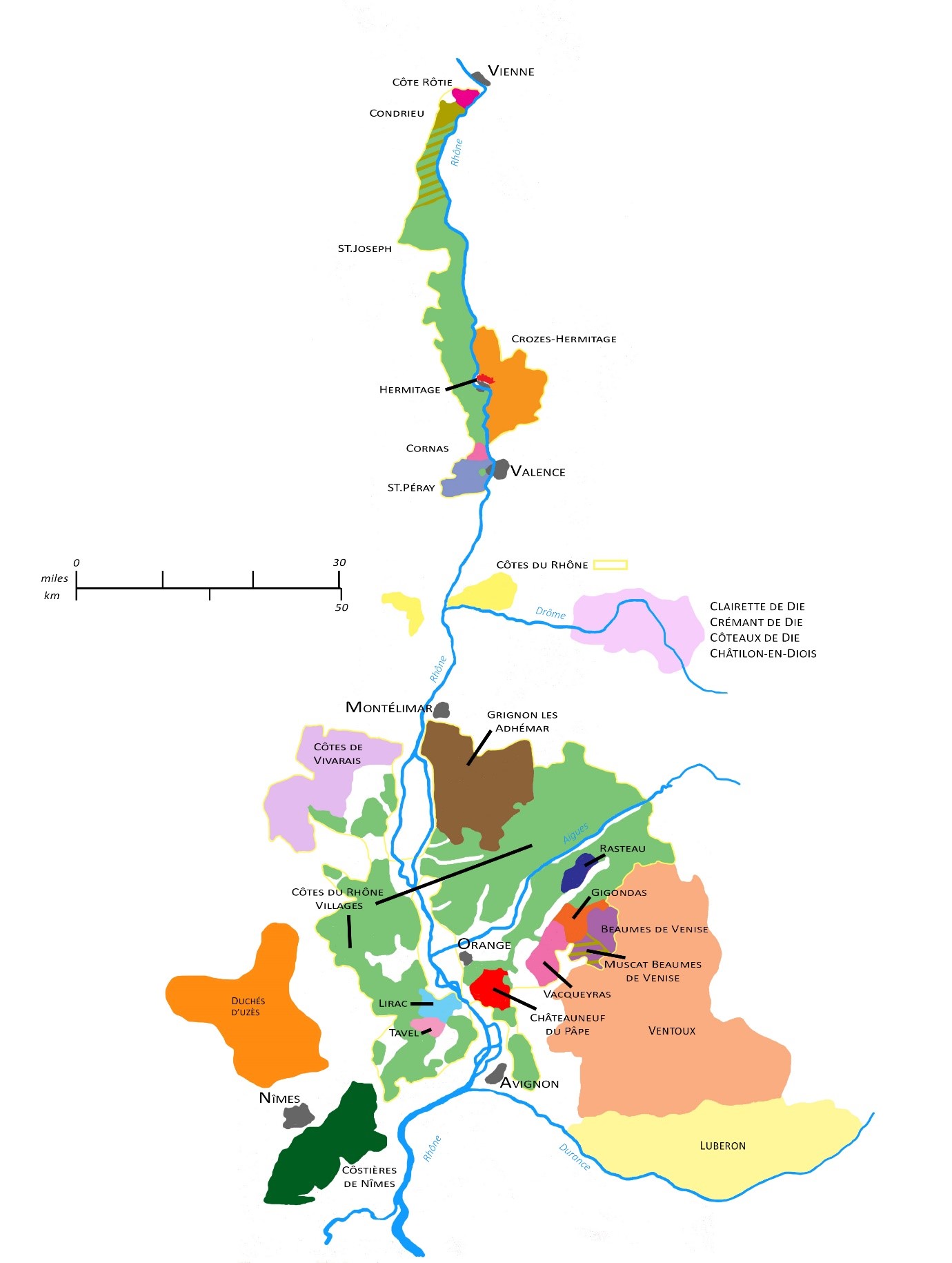

The valley can be split into two halves, the north (known as septentrional in France), which runs from Côte Rôtie, just to the south of Vienne, to the confluence with the river Drôme a little south of Valence. There is then a 20km area with no vines before the southern (meridional) area, which runs as far south as Avignon. The north is cooler, with a steep sided valley and vines perching on terraced slopes, whilst the south is broader, rolling countryside and has the sun-baked feel of the Mediterranean. By far the majority (well over 90%) of wine is made in the south.

Reds in the north are made with Syrah, and it is here that the very greatest wines are made, whilst in the warmer south, Grenache dominates, supported by Syrah, Mourvèrdre in the warmest spots, and up to 9 other permitted varieties. Rosés are generally inexpensive and easy going, with the exception of Tavel, an appellation solely for rosé, whose wines tend to more body and structure than most. White wines are mostly based around Marsanne, Roussanne, Grenache Blanc and Clairette (although there are a further 10 authorised varieties) and are generally quite rich and textural, with savoury fruit character. The star white wine is Condrieu (and a few copies made on the hills just outside the appellation), a barrel fermented viognier that stands alone as the world’s finest example of the grape.

History

The Rhône lays claim to being France’s oldest wine region and the earliest definite records of wine production in the valley were made by Pliny in the 1st century AD, who wrote highly of the red wines made near Vienne (about where Côte Rôtie now is). The Roman occupation was the heyday for the Rhône in general and after the Gauls took control again, there are few records, although it is probable that by the 11th century the land was mostly controlled by the church. During the medieval period wines from here rose to fame again, notably when Pope Clement V moved the papal court to Avignon in 1309 bringing lasting fame to Châteauneuf du Pape, which was widely consumed at court. At this point in history, all wine travelled any distance by river and between the 14th and 16th centuries, whilst the wines remained popular to the south, Burgundy, threatened by the quality of the wines, banned their import to the Duchy. This effectively cut off the Parisian and valuable northern French markets, along with England and Holland. It would not be until the Canal du Midi opened in 1681 that a route (through Bordeaux) to the north was opened again. Interestingly this led to the practice of adding some Hermitage to Bordeaux to give it more body and ripeness and these Hermitagé wines were seen as superior. By 1710 the Loire had become navigable from St Etienne and Rhône wines once again were seen in Paris.

Châteauneuf was the first region to set out production rules in 1923 which were the basis of the appellation contrôlée rules, of which it was the first recognised in 1936. For much of the 20th century, the Rhône was not widely known and whilst some superb wines were made in Hermitage, which had a small following, the region as a whole did not excel itself with robust and alcoholic wines common. With financial returns slender, much of the best land (which was the hardest to farm) was abandoned and exports were a little over 1 million cases (compared to 8 million today). By the early 1970’s Côte-Rôtie was moribund, with only 70 hectares planted and little market for the wine. Most Rhône wine was bottled and marketed by négociant houses, even that made by the co-operatives ended up there and financial returns were poor. The next 20 years saw a turnaround in fortunes, with the few estate wines starting to receive the recognition they deserved, none more so than the wines of Guigal in Côte-Rôtie, aided by his relentless promotion of his wines. As prices rose slowly, more growers started to make and bottle their own wine, often to great acclaim and momentum built. It has taken longer for this effect to spread into the south, but more and more high quality wine is being bottled and as the area, with the exception of a few names, is still not one for speculators, much of this wine is fairly priced for the drinker as opposed to the investor.

Grape Varieties

In all Rhône appellations, grape varieties are listed either as Main, Supplementary or Accessory (except Châteauneuf-du-Pâpe where all permitted varieties are considered ‘main’). Rules vary from AOC to AOC, but generally main varieties will have to make up between 75-90% of the final wine. Below is a list of all varieties allowed and their status in appellations.

Red

Brun Argenté – Main in Châteauneuf, Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Rasteau & Vacqueyras.

Calitor – Accessory in Tavel.

Carignan – Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Lirac, Rasteau, Tavel & Vacqueyras.

Cinsault – Main in Lirac and Châteauneuf, Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Rasteau, Tavel & Vacqueyras.

Clairette Rose – Main in Tavel and Châteauneuf, Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Rasteau, & Vacqueyras.

Counoise – Main in Châteauneuf, Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Rasteau & Vacqueyras.

Grenache Noir – Main in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Châteauneuf, Gigondas, Lirac, Rasteau, Tavel & Vacqueyras.

Marselan – Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône.

Mourvèrdre – Main in Châteauneuf, Lirac & Tavel. Supplementary in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Gigondas & Vacqueyras, Accessory in Beaumes de Venise & Rasteau.

Muscardin – Main in Châteauneuf, Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Rasteau & Vacqueyras.

Piquepoul noir – Main in Châteauneuf & Tavel, Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Rasteau & Vacqueyras.

Syrah – Main in Châteauneuf, Lirac & Tavel. Supplementary in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise Gigondas & Vacqueyras, Accessory in & Rasteau.

Terret Noir – Main in Châteauneuf, Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Rasteau & Vacqueyras.

White

Bourboulenc – Main in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Châteauneuf, Lirac, Tavel & Vacqueyras. Accessory in Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas and Rasteau.

Carignan Blanc – Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Lirac, Rasteau, Tavel & Vacqueyras.

Clairette Blanche – Main in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Châteauneuf, Lirac, Tavel & Vacqueyras. Accessory in Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas and Rasteau.

Grenache Blanc – Main in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Châteauneuf, Lirac, Rasteau, Tavel & Vacqueyras. Accessory in Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas.

Grenache Gris – Main in Châteauneuf, Rasteau, Tavel. Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise Gigondas & Vacqueyras.

Marsanne – Main in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages & Vacqueyras. Accessory in Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Lirac Rasteau & Vacqueyras.

Muscardin – Main in Châteauneuf. Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Rasteau & Vacqueyras.

Muscat Blanc à Petit Grains – Main in Muscat Beaumes de Venise.

Picardan – Main in Châteauneuf.

Piquepoul blanc – Main in Châteauneuf and Tavel. Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Lirac & Rasteau.

Piquepoul gris – Main in Châteauneuf and Tavel.

Roussanne – Main in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Châteauneuf & Vacqueyras. Accessory in Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Lirac & Rasteau.

Ugni Blanc – Accessory in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages, Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Lirac & Rasteau.

Viognier – Main in generic Côtes-du-Rhône & villages & Vacqueyras. Accessory in Beaumes de Venise, Gigondas, Lirac & Rasteau.

Climate

The climate differs markedly from north to south, but there is one constant, wind. The famed Mistral blows from north to south and often tears down the valley, meaning the best vineyard sites need to offer some protection from its potentially damaging gusts. In Côte-Rôtie, vines are traditionally trained as pairs to provide more strength against this near constant wind. What it does bring, however, is lower disease pressure as it keeps the vineyards dry and it acts as a cooling agent in the region maintaining freshness in the wines.

With a continental climate of bitter winters and hot dry summers, the northern Rhône is considerably cooler than the south and in lesser vintages, Syrah can struggle to attain ripeness before autumn cold sets in (indeed the Northern Rhône marks the most southerly point that chaptalization is still permitted). Those who haven’t drunk them frequently think Hermitage and Côte-Rôtie are big and rich wines, yet they are Syrah at its most vivacious, aromatic and elegant, nothing like big bruisers from hot climates. In contrast, the Southern Rhône is markedly Mediterranean and without the wind would feel Provençal. Long hot summers and mild wet winters are the norm and a lack of water, rather than a lack of heat is more of a potential problem. Early autumn rains can be an issue for the higher vineyards (and the whole region in 2002), but it is generally a benign climate for wine production and suffers less vintage variation than the north.

Winemaking

Whilst oak has traditionally been used for the better reds in the whole region, very little of it was new. During the 1980s new barrels began to make an appearance, especially at Guigal who ages some of his cuvées in 100% new oak and whilst the quantity of new oak at most estates has now moderated, it is still common to see some used for top Syrahs in the north. Grenache has less affinity for barrel and most of the wines from this grape are matured in concrete vats, although some, especially in Châteauneuf, use big old barrels for maturation. Whites from Viognier often see plenty of new wood whilst older oak is more commonly used for other whites (although Hermitage, notably that from Chapoutier, may see lavish amounts of new oak). Improved viticulture and techniques in the winery, notably cooler fermentations, has improved the quality of white Rhône dramatically over the past 30 years and whilst they are often quite ‘thick’ textural wines, they shouldn’t lack freshness.

The Appellations of the Rhône

The Northern Appelations

Côte Rôtie

Key info: Vineyard area: 323 Ha; Varieties permitted: Syrah, Viognier (up to 20%); Production in cases (2019): 134,700.

Possibly the oldest wine producing region in France and considered by many to be the finest expression of Syrah in the world, as recently as the 1970s Côte Rôtie made few wines of merit, with the majority of production going through négocients. The terrain here is extremely steep and difficult to work, yields are low and the rewards for farming here were so marginal that vineyard area had dropped to just 70 Ha. One man, Marcel Guigal, resurrected the appellation, with tireless promotion and his single vineyard wines showing the world just what was possible here. By the mid-1990s the vineyard area had reached 150 Ha and as prices have risen, this has continued to increase, with much of the new planting on the plateau above the slopes where fruit does not ripen as fully and which have somewhat diluted the overall quality of the appellation.

The vineyards face south-east and are located in a steep valley just below a sharp bend in the river, protecting them from the cold northerly winds and providing maximum sun exposure. Terracing is essential here owing to the slope and vines. Traditionally the vineyards were divided into Côte Brune and Côte blond, the former with more clay making sturdier and more structured wines. Until recently, most wines were a blend of the two, however the rise of site specific bottlings has meant wines from each terroir are more available for comparison. The most famous site specific bottlings are Guigal’s La Mouline (Côte Blonde) and La Turque and La Landonne (Côte Brune), however these are wines of great power and full of oak and are not necessarily ‘traditional;’ Côte Rôtie, which should be a wine of aromatic charm and finesse.

Although up to 20% viognier is allowed to be co-fermented with the Syrah here (giving a floral character and softer tannins) in practice few use more than 10% and the majority are between 2-5%, with more and more omitting it completely.

Condrieu

Key info: Vineyard area: 203 Ha; Varieties permitted: Viognier; Production in cases (2019): 82,700.

Indisputably home of the world’s greatest viognier, owing to the difficulty of growing the grape and the poor financial returns compared to other fruit crops, this appellation had almost ceased to exist by the 1960s with only 12 Ha officially in production. The theoretical area permitted for the appellation overlaps the northern part of St Joseph and is quite large, but because of the sensitive nature of the variety, only sheltered spots are suitable for it. Wines from the northern part are especially rich, but all Condrieu should have relatively high alcohol, a rich texture, moderate acidity and a haunting florality.

Much Condrieu has noticeable new oak, though portions vary wildly between producers, as does the use of malolactic fermentation. Yields are notoriously low which partly explains the high prices of the wine. At one time, the wines from here were sweet and this tradition has been resurrected by a handful of growers, notably Yves Cuilleron. Guigal is the dominant force, but arguably the finest wines are made by Georges Vernay.

Château Grillet

Key info: Vineyard area: 3.5 Ha; Varieties permitted: Viognier; Production in cases (2019): 690.

One of the country’s smallest appellations and under single ownership (since 2011 by François Pinault, owner of Latour), this sheltered amphitheatre historically produced the world’s greatest viognier and the only one that benefitted from 10 years ageing. After many years of mediocrity, there are signs that it might once again justify its high price.

St.-Joseph

Key info: Vineyard area: 1,348 Ha; Varieties permitted: Syrah (with up to 10% Marsanne or Roussanne) for reds, Marsanne, Roussanne for whites; Production in cases (2019): 481,300 red, 76,500 white.

A rapidly growing appellation that covers the west bank of the Rhône from Cornas in the south up to Côte Rôtie in the north, with a small pocket on the outskirts of Valence. Planting here has grown six fold over the last 50 years and most of the wine made is charming and fruity and considerably lighter than other local Syrahs, mostly owing to the cooler eastern exposure of the newer vineyards. Much of the wine made under the St.-Joseph appellation is overpriced and whilst perfectly charming, is of no great distinction. The exception to this is in some of the vineyards around Condrieu in the north and most importantly in the original heart of the appellation planted with (up to 100 years) old vineyards on terraces around Tournon, facing Hermitage. Here St.-Joseph can produce rich, peppery Syrah, perhaps without the tannic backbone of Hermitage, but still with fine ageing potential, Chave’s is a benchmark example..

Crozes-Hermitage

Key info: Vineyard area: 1,778 Ha; Varieties permitted: Syrah (with up to 15% Marsanne or Roussanne) for reds, Marsanne, Roussanne for whites; Production in cases (2019): 559,500 red, 84,200 white.

The biggest appellation of the northern Rhône runs for around 15km north to south around the hill of Hermitage on the east bank of the river. In an appellation this size, there is a lot of very ordinary wine made, often by merchants, however average quality is much higher than St Joseph and the late 1980s saw a new generation of ambitious producers emerge driving the region forward and attracting higher prices.

Although white grapes are permitted, in practice any decent Crozes is 100% Syrah and many see some barrel ageing. The richer soils mean the wines are softer and fruitier than those of Hermitage, but the best can still justify 10-15 years of bottle ageing. The very best wines, historically led by Jaboulet’s Domaine de la Thalabert and joined by Graillot, Colombier and Pochon, tend to come from the communes of Chassis and Chanos-Curson, just to the south and east of Tain l’Hermitage, although recent promise has been shown on the plateau above Hermitage itself.

Whites are often fairly undistinguished, although those grown around Mercurol can have some real density of stone fruit and rich texture.

Hermitage

Key info: Vineyard area: 140 Ha; Varieties permitted: Syrah (with up to 10% Marsanne or Roussanne) for reds, Marsanne, Roussanne for whites; Production in cases (2019): 36,900 red, 17,400 white.

Around 50km south of Côte-Rôtie lies the hill of Hermitage, a south facing block of granite that has been famous for as long as Bordeaux for the quality of its wines. This small appellation (Château Lafite is 107 hectares and often produces more wine) sits on a steep slope sheltered from the cool northerly winds on a bend in the river. Whilst not as precipitous as Côte-Rôtie, the slope still requires terracing is some parts and with mechanization outlawed, there is an annual back breaking task of moving the eroded soil back up the slope each year. As it has remained famous and in demand for so long, there is no land left to plant and ownership is dominated by four producers – Chave, Jaboulet, Chapoutier and Dèlas.

Whilst in theory white grapes are permitted in the red wine, in practice none are used. There are 12 distinct climats on the hill with those in the west generally making more structured wines than those in the east. Arguably the greatest are Béssards, Méal and Gréffieux. Producers traditionally owned vines in many different climats and blended across them, indeed the greatest of them all, Jean-Louis Chave still exclusively does this, however recent years has seen an urge (probably financially motivated), to start bottling multiple wines from individual plots.

Traditionally new oak was not used here, although it has crept into some cellars in recent years. The reds of Hermitage should always be impressive and have massive concentration, tannin and rich aromatics when young and can age for decades, developing haunting tertiary flavours.

Whites are less common and winemaking styles vary considerably, however all have in common great body and the best age magnificently.

Cornas

Key info: Vineyard area: 156 Ha; Varieties permitted: Syrah; Production in cases (2019): 57,000.

Another 10km south of Hermitage and also on steep granite slopes lies Cornas, for long thought of as the rustic country cousin of Hermitage and with only one producer of note, Auguste Clape, whose very tannic and traditional wines need years of bottle age to be approachable. The late 1980s saw a revival of interest in the area and new producers began to appear, challenging the historic perceptions of the region and making powerful but less wild wines. Outside of Clape, the best wines now tend to be richly fruited, quite luscious and backed by rich tannin.

Whilst prices have risen, quality is not far behind that of Hermitage and from the best producers, notably Jean-Luc Colombo, Domaine Courbis, Eric and Joel Durand, Vincent Paris and Domaine de Tunnel, these still offer compelling value in the global context of fine wine.

St.-Péray

Key info: Vineyard area: 92 Ha; Varieties permitted: Marsanne, Roussanne; Production in cases (2019): 39,800.

On the opposite bank to Valence and the final cru in the northern Rhône, St.-Péray Soils are mostly granite and stones and this is a relatively warmer spot making still and sparkling whites from Marsanne and Roussanne. In recent times, less sparkling is being made (acidities here do not tend to favour sparkling production) and a few ambitious producers, mostly from outside the appellation, are making some truly fine whites here that can rival Hermitage for complexity and balance, albeit in quite an exotic package.

Clairette de Die/Crémant de Die

Key info: Vineyard area: 1,658 Ha; Varieties permitted: For reds, Grenache noir must make up 40%, with Syrah and Mourvèdre together at least 15%. These three varieties must make up 70%, with up to 30% of the other permitted varieties. Whites must be a minimum of 80% from Bourbelanc, Clairette, Grenache Blanc, Marsanne, Roussanne & Viognier. Ugni Blanc and Picpoul are authorised up to 20%; Production in cases (2019): 958,700 Clairette, 11,900 Crémant.

In the 19th century this was a significant appellation, but it is now much smaller and mostly consumed locally. The local co-operative makes 75% of the production. Clairette Brut is made by the transfer method and is generally a fairly neutral sparkling, Crémant is superior, being made by the traditional method and must be a blanc de blancs. Clairette de Die tradition is more interesting as it is a minimum 75% Muscat and made by a variation of the ancestral method, where the wine is bottled before fermentation is complete making it sparkling and with residual sugar.

Châtillon-en-Diois/Côteaux de Die

Key info: Vineyard area: 1.5 Ha Côteaux de Die, 43 Ha Châtillon-en-Diois; Varieties permitted: Clairette for Côteaux de Die, Gamay, Chardonnay and Aligoté for Châtillon-en-Diois; Production in cases (2019): 610 white for Côteaux de Die; 6,500 red, 11,400 white and 3,200 rosé for Châtillon-en-Diois.

Côteaux de Die is a miniscule appellation with just 1.5Ha currently planted. It is a still light white made from Clairette. Châtillon is the appellation for some bracing and light still wines made around the town of Die, rarely seen outside of the locality.

Côtes-du-Rhône

Key info: Vineyard area: 30,281 Ha; Varieties permitted: For reds, Grenache noir must make up 40%, with Syrah and Mourvèdre together at least 15%. These three varieties must make up 70%, with up to 30% of the other permitted varieties. Whites must be a minimum of 80% from Bourbelanc, Clairette, Grenache Blanc, Marsanne, Roussanne & Viognier. Ugni Blanc and Picpoul are authorised up to 20%; Production in cases (2019): 12.72 million red, 1.25 million rosé, 828,700 white.

France’s second largest appellation, after Bordeaux AOC, and one that covers a vast area, encompassing the whole valley. Whilst soils and climates vary wildly over such a geographically large appellation, there are some fine wines sold under this label, although the vast majority is cheap, ordinary, but generally reliably fruity and decent value as everyday drinking. Most of the production centres around the arid plains of the southern valley and is made by cooperatives. Whites and rosés have improved considerably over the past 20 years as investment in more modern winemaking equipment has borne fruit.

Côtes-du-Rhône Villages

Key info: Vineyard area: 9,152 Ha; Varieties permitted: For reds, Grenache noir must make up 50%, with Syrah and Mourvèdre together at least 25%. These three varieties must make up 80%, with up to 30% of the other permitted varieties. Whites must be a minimum of 80% from Bourbelanc, Clairette, Grenache Blanc, Marsanne, Roussanne & Viognier. Ugni Blanc and Picpoul are authorised up to 20%; Production in cases (2019): 3.61 million red, 27,700 rosé, 113,800 white.

A distinct step up from generic Côtes-du-Rhône, there are 95 communes from which the villages wine may come, with stricter production laws and theoretically better terroirs. The best 17 of these communes are also allowed to put the village name on the label, with Cairanne and Séguret the two most likely to follow Gigondas, Vacqueyras, Rasteau, Vinsobres and Beaumes de Venise in being promoted to full AOC in due course. Villages wines from conscientious domaines can offer some of the best value wine in the world.

The Southern Appelations

Côtes de Vivrais

Key info: Vineyard area: 232 Ha; Varieties permitted: Grenache Noir (min 30%) and Syrah (min 40%) plus other authorised Rhône varieties, along with Clairette, Grenache Blanc and Marsanne for whites; Production in cases (2019): 52,300 red, 39,300 rosé, 6,400 white.

The furthest north of the southern Vivarais was granted AOC status in 1999. Half of the wine is red, 45% rosé and just 5 % white. 90% of production is handled by cooperatives and the wines are light and simple and rarely seen in the UK.

Grignan-les-Adhémar

Key info: Vineyard area: 1,318 Ha; Varieties permitted: The whole Rhône palette, although none may be more than 80% of the final blend for reds, 60% for whites; Production in cases (2019): 433,900 red, 95,100 rosé, 83,000 white.

This appellation name replaced that of Côteaux du Tricastan in 2010, as Tricastan was too readily associated in the domestic market with the massive nuclear power complex of the same name (and which the AOC overlooks) which suffered a uranium leak in 2008. Cooler than much of the southern Rhône the wines from here are lighter and often strawberry scented and can be very appealing, not unlike those of Ventoux.

Vinsobres

Key info: Vineyard area: 570 Ha; Varieties permitted: Grenache noir must make up 50%, with syrah and mourvèdre together at least 25%. These three varieties must make up 80%, with up to 30% of the other permitted varieties; Production in cases (2019): 210,500.

This Village was promoted to full AOC in 2006 and its relatively high and cool vineyards are especially suited to rich, peppery syrah. More fragrant and fresher than many southern appellations, the wines from here can be very fine value.

Rasteau

Key info: Vineyard area: 949 Ha; Varieties permitted: Grenache noir must make up 90%, with the other Rhône permitted varieties making up 10%; Production in cases (2019): 359,900.

High class village that has an AOC for its rare fortified wine as early as 1934 and which was promoted to AOC in 2009 for its still reds. Many are made from 100% Grenache and the best are easily equal of Châteauneuf du Pâpe and generally superior (yet cheaper) than those of Gigondas. Rich spicy and powerful with decent ageing ability, they should be better known.

Gigondas

Key info: Vineyard area: 1,208 Ha; Varieties permitted: Grenache noir up to 80%, with a minimum of 15% from syrah and/or mourvèrdre. The other Rhône permitted varieties (minus carignan) making up 10% maximum; Production in cases (2019): 397,800 red, 2,800 rosé.

The first of the villages to be promoted to AOC in 1971, Gigondas is renowned for the power of its wines rather than for finesse. Producers with vineyards higher on the plateau can make wines that are eerily like great Châteauneuf, whilst those in the lower lying vineyards tend to produce quite dark wines that can approach fortified alcohol levels. Prices here have been steadily on the rise and now nearly match those of Châteauneuf.

Vacqueyras

Key info: Vineyard area: 1,440 Ha; Varieties permitted: Grenache noir up to 80%, with a minimum of 15% from syrah and/or mourvèrdre. The other Rhône permitted varieties (minus carignan) making up 10% maximum; Production in cases (2019): 482,100 red, 5,500 rosé, 23,200 white.

The second of the villages to be promoted to AOC in 1990, Vacqueyras makes a slightly lighter style than its neighbours. Often notably spicy and laden with raspberry and dark cherry fruit, many have slightly rustic tannins, probably more down to old fashioned winemaking than terroir.

Beaumes-de-Venise & Muscat Beaumes de Venise

Key info: Vineyard area: 675 Ha for table wine, 332 Ha for VdN; Varieties permitted: Grenache noir minimum 50%, with a minimum of 25% from syrah and/or mourvèrdre. The other Rhône permitted varieties making up 20% maximum. Muscat blancs a petit grains for VdN; Production in cases (2019): 238,100 red, 61,800 VdN.

Muscat Beaumes de Venise was granted an AOC in 1943, but records of production of Muscat here date back 2000 years. It is made by adding spirit to the fermenting must, fortifying to 15% and leaving around 100g/L of residual sugar. It tends to be more refreshing and delicate than Languedoc VdN’s.

Red wines from the commune received their AOC in 2005 and they tend to be spicier and slightly lighter than other appellations in the region, owing to the altitude of many of the vineyards. The majority is produced at the cooperative, but there are also 15 individual domains making wine of noteworthy value.

Lirac

Key info: Vineyard area: 857 Ha; Varieties permitted: Grenache noir 40%, with a minimum of 25% from syrah and/or mourvèrdre. The other Rhône permitted varieties making up the rest with a 10% maximum for Carignan; Production in cases (2019): 202,910 red, 7,700 rosé, 22,800 white.

On the west bank of the Rhône, opposite Châteauneuf, Lirac was formerly famous for its very full bodied rosé, but is now better known for its soft and slightly earthy red wine. An AOC since 1945, it is only in the past 20 years than wine of quality has started to appear and whilst the majority tend to lack the structure of the best southern Rhône wines, they make up for that in generosity and value.

Châteauneuf-du-Pâpe

Key info: Vineyard area: 3,200 Ha; Varieties permitted: For red, Cinsaut, Counoise, Grenache noir, Mourvèdre, Muscardin, Piquepoul noir, Syrah, Terret noir, Vaccarèse. For white, Bourboulenc, Clairette blanche, Clairette rose, Grenache blanc, Grenache gris, Picardan, Piquepoul blanc, Piquepoul gris, and Roussanne. There are no legal limits as to proportions in red or white or distinctions between them; Production in cases (2019): 813,000 red, 61,100 white.

Globally the most famous appellation of the Rhône and the finest in the south, it was the birthplace of the appellation d’Origine system in the 1920s and produces the country’s most powerful wines. Although theoretically a wine could be made from 100% Picpoul, in practice reds are overwhelmingly made of Grenache noir, with Mourvèrdre becoming increasingly popular as a seasoning, with whites mostly dominated by Grenache Blanc, Clairette and Bourbelenc. Although famous for the large galet stones, which store and radiate heat back to the vines, soils are actually very varied and Château Rayas, for example, has not a stone in sight and is mostly on limestone. Traditionally, producers had parcels in several communes and blended across the appellations, however, like other regions, the rush for premium cuvées and premium prices has meant the rise of single plot bottlings usually at a heavy price premium. Stylistically, the wines are generally very high in alcohol and quite high in tannin and can be foreboding in youth. Those with the requisite balance soften with age, taking on a gamey richness to underlie the dark berry fruit and spices. Sadly, too many wines today that are impressively extracted and powerful on release, lack the balance to mature to greatness. Undoubtedly capable of producing one of the world’s great fine wines (see Vieux Telegraphe, Beaucastel, Domaine de la Janasse, Rayas and on occasion Font Redon, Foria, Pegau and Vieux Donjon), too much has been blowsy and overpriced. Its fame however ensures a willing market.

The whites are very varied in style, but tend to be quite low in acidity, full bodied and more textural than aromatic. Few benefit from age and few justify their price, although recent vintages have seen more producers making a slightly fresher style – a welcome development.

There are 320 grower producers in Châteuneuf, with only 5% of the crop vinified at the co-operative. 27% of the vineyard area is currently certified organic.

Tavel

Key info: Vineyard area: 898 Ha; Varieties permitted: Grenache Noir, Cinsault, Syrah, Mourvèrdre, Clairette, Picpoul Blanc, Picpoul Noir, Borboulanc; Production in cases (2019): 332,000 rosé.

On the west bank of the Rhône and a rare all rosé appellation, Tavel has very sweet fruit, owing to the great warmth in the vineyards, high alcohol, but is always bone dry. The first famous rosé, it has for years lived on its laurels and it is almost never good value, although the same could now be said of famous names from Provence. The best two producers are Château d’Acqueria and Domaine de la Mordorée, with the latter making a fresher more balanced style.

The following are appellations administratively included in the Rhône, but outside of the valley proper.

Côstières de Nîmes

Key info: Vineyard area: 3,880 Ha; Varieties permitted: For red, Grenache noir minimum 25%, syrah and mourvèrdre minimum 20%, maximum of 40% Carignan, maximum of 40% cinsault. For whites, Bourboulenc, clairette blanc, grenache blanc, maccabéo, rolle, roussanne and ugni blanc (maximum of 30%); Production in cases (2019): 986,200 red, 84,000 rosé, 143,300 white.

Historically this was grouped with the Languedoc, however the grape varieties, soil, topography and style of the wines was much more akin to the Rhône, so it is now considered a part of that. Although it is less dominated by cooperatives than other southern regions, this was traditionally a producer of bulk wines, however recently many domaines have started estate bottling and this is a dynamic and very good value source of wine. The soils and climate are relatively homogenous and the wines are similar to good Côtes-du-Rhône.

Côtes de Ventoux

Key info: Vineyard area: 5,691 Ha; Varieties permitted: For red, Grenache noir, cinsault, syrah, mourvèrdre, and carigna must make up 80% (with carignan a maximum of 30%). Other permitted Rhône varieties can make up the balance. For whites, Clairette, Bourboulenc, Grenache blanc, and Roussane (maximum 30%); Production in cases (2019): 1.52 million red, 1.12 million rosé, 161,400 white.

Located on the western and southern flanks of the imposing Mont Ventoux (which has a significant cooling effect) this growing appellation is more successful with Syrah than most of its southern counterparts. Historically dominated by cooperatives making very light and fruity vin ordinaire, there are an increasing number of ambitious estates making generous and good value wines.

Côtes de Luberon

Key info: Vineyard area: 3,397 Ha; Varieties permitted: At least 60% grenache noir & syrah (10% minimum syrah) plus cinsault and carignan (maximum 20% of each). Balance can come from Counoise, Gamay noir, Mourvèdre, Pinot noir. For whites, Ugni blanc (maximum 50%), Roussanne & Marsanne (combined maximum of 20%), Clairette, Grenache blanc, Vermentino, and Bourboulenc; Production in cases (2019): 393,700 red, 1.04 million rosé, 278,900 white.

Somewhere between the Rhône and Provence, both geographically and vinously (as seen by the amount of rosé made here), the AOC was created in 1988 and produces lightish reds (although some have shown it is possible to make richer, herb scented wines in the mould of Provençal reds), some decent whites (aided by the cooler nights here) and rosé that can match Provence for quality but at a much more competitive price.

Duché d’Uzès

Key info: Vineyard area: 322 Ha; Varieties permitted: Syrah (minimum 40%), Grenache noir (minimum 20%), Carignan, Mourvèdre, Cinsault. Viognier (minimum 40%), Grenache Blanc (Minimum 30%) plus Marsanne, Roussanne & Vermentino (minimum 20% between them). Clairette & Ugni (up to 10% between them); Production in cases (2019): 65,400 red, 23,700 rosé, 29,200 white.

Promoted to AOC in 2012, this geographically large area is sparsely planted with vines and lies in the far west of the southern Rhône. The vast majority of the vineyard are lies just to the west of the town of Uzès and there are less than 50 producers, so international recognition is virtually zero and yet the wines from here are some of the most characterful and interesting in the southern Rhône, being quite rich yet also refined, whilst the whites are exotic and flavoursome. This appellation deserves more recognition.

Market

The entire region produced 4.5 million hectolitres of wine (around 50 million cases) in 2019, of which 2.8 million were appellation wines, second only to Bordeaux (with 4.9m Hl of AOC wine). This was up on 2017 and 2018, but slightly below the 6 year average. Just under half of the AOC wine is basic Côtes-du-Rhône, with a further 12% Côtes-du-Rhône Villages. Red wine made up 75% of production, rosé 15% and whites 10%. The last few years have seen a significant increase in the production of both white and rosé. Vineyard area grew slowly in the first part of the 2010s but has since declined nearly 4% to stand at 67,628 hectares. Global sales of Rhône wine have declined over the past few years with only the appellations Beaumes-de-Venise and Cairanne recording significant growth. Although individual domains make up 80% of the 2,200 producers in the Rhône, they make only 33% of the wine, with the rest made by cooperatives. Nearly two-thirds of all of the wine produced is sold to the market by merchants and négocients.

Two thirds of Rhône wine is consumed domestically (half of that sold in supermarkets), whilst a third is exported. The USA has overtaken the UK to become the most important export market for both volume and value with a big increase in sales of the top Northern crus in the last 5 years. Half of all exports go to the USA, UK and Belgium, with these three countries even more important for the more premium wines.

Just over 28% of the vineyard area is certified Organic, with a further 10% in conversion.

Recent Vintages

Whilst vintage variation plays less significance than in many European countries, there are differences to note, especially in the finest wines. 20th century vintages not mentioned are likely no longer of interest.

1978 – Probably the greatest vintage of modern times. Highly prized and now very expensive, the best Hermitage is only now reaching full maturity. In the south the best are still going strong.

1983 – Outstanding and tannic wines in the north still going strong now. Fine Châteauneuf mostly faded.

1988 – In the north a fine vintage overshadowed by the two that followed. Mature now. In the south, a classic. Fine wines that are still drinking now.

1989 – In the north rich and opulent and drinking well now. In the south, High quality and with good structure. Many are still going strong.

1990 – In the north, massive and tannic wines that are still not ready. Hermitage better than Côte-Rôtie. In the south, exceptional but very heady and with lowish acidity. Most are past their best.

1991 – The north was one of the few areas of France to have a good vintage. Exceptional in Côte-Rôtie. Poor in the south.

1995 – In the north and the south, a fine vintage drinking well now.

1998 – In the north, wines were tannic and tough. Many will never be charming, but the best may make great old bones. In the south, at the time this was being described as one of the best ever, however the wines have not matured as well as expected and are a bit angular.

1999 – In the north, an exceptional vintage, in the south very variable.

2000 – Good to very good vintage that are mostly starting to fade.

2001 – In the north a very fine vintage with finesse and freshness. Still improving. In the south, a highly acclaimed vintage with high levels of colour and tannin. Some lacked acidity but the best will keep for years yet.

2002 – Heavy rainfall before and into harvest left dilute and raw wines. Whites were ok, the rest should have been drunk long ago.

2003 – Extreme heat saw wines in the north of great concentration and structure. Atypical, but many have aged quite well. In the south the wines were excessively alcoholic and few have made old bones.

2004 – Reasonable quality but only the best still worth drinking.

2005 – In the north and the south a great vintage that will benefit from further age.

2006 – In the north this was a good to fine vintage, with ample concentration and ripe tannins. Drinking now but will keep. In the south, a successful vintage with rich, hedonistic wines. Not for further cellaring.

2007 – In the north an uneven growing season but a fine autumn led to decent wines. At best now. In the south, very ripe with soft tannins. To drink now.

2008 – In the north, rains led to a dilute and dull vintage. Hopefully all drunk by now. n the south, weak reds and also best drunk by now. Whites were reasonable.

2009 – In the north a very fine vintage that is perhaps a little over ripe. In the south, impressive and very powerful after a hot summer, but often over alcoholic.

2010 – In the north this was an exceptional year, perhaps as good as 1978. In the south, outstanding for reds and whites.

2011 – In the north, September rain diluted what may have been a very good vintage. Pleasant wines for earlier drinking. In the south, decent quality but many wines had drying tannins.

2012 – In the north a decent vintage with lower alcohols than normal unusually in combination with lower acidities. Fairly tannic wines that may turn out well. In the south, a ripe vintage with low acidities. Attractive but not necessarily age worthy.

2013 – In the north very good reds were made with high acidities promising long life. In the south, small yields but overall good quality.

2014 – In the north this was a lighter vintage, with attractive fruit but without the concentration for long ageing. Whites were good. In the south very late harvest and lighter wines, but not without charm and finesse

2015 – Very ripe fruit in the north. Where acid levels are high enough, this looks to be a good to great year. In the south, small yields, high alcohols, but fine quality.

2016 – Superb in the north with more freshness than 2015. Low yields in Hermitage. One of the greats in the south. Very ripe and concentrated.

2017 – In the north this is remembered as a difficult vintage that produced outstanding wines, better than 2015 and the equal of 2016. In the south, a small crop with ample ripeness but plenty of skins which has made for some well-structured and age-worthy wines.

2018 – A hot year but in the North acidities seem to have held and the wines look very promising. Whites are for more immediate drinking. In the South it was a small crop but quality was very high, albeit with lowish acidity.