An Introduction To: Spain

· Maggie Macpherson Maggie Macpherson on

Jeroboams Education is a new series on our blog providing you with the lowdown on the most iconic wine producing regions of the world. Led by our super buying team, Peter Mitchell MW and Maggie MacPherson will introduce you to the key facts and a little history of all the regions you recognise but perhaps don’t know too well. To help really further your education, why not drink along? Browse our Spain selection.

Introduction

We Brits love Spain. We love it so much that around 18 million of us visited the country in 2019, meaning we are the main country of origin for Spain’s tourism industry. So why do we love it so much?

Firstly, it over-delivers on price with regards to everything really – beautiful beaches, top quality food and of course delicious wines can be found in Spain at all price points. Secondly, sun, Spain’s coastal areas receive more than 300 days of sunshine each year, perfect for the sun worshiping Brits and grapes. Thirdly, there are still hidden gems to be found. Such as the Galician port of La Coruna and the wine revolution that is still taking place, with renegades working outside the DO system in the pursuit of the next big thing. Oh, and finally, how can I not mention the food scene?! It is widely accepted that San Sebastian is the world’s best city for foodies, and great food deserves excellent wine. Lucky Spain has it in buckets, quite literally, as the country with the world’s largest vineyard area with almost 1 million Ha planted under vine, although the drier climate and poorer soils result in lower production levels than France and Ital

So, I guess I drew the short straw, or more appropriately the long straw, as there is no easy and quick way to sum up Spain as a winemaking country. From the beautifully fragrant whites from the Northeast, through the hotbed of rustic reds produced in the central plateau finishing with the crisp Cava’s of Cataluña, there is a veritable smorgasbord of wines produced across Spain at every price point! This document aims to give a brief overview of the key regions excluding the sherries of Jerez as these will be covered in the Fortified training.

History

As with much of the Mediterranean winemaking was introduced by the Phoenicians around 1,000 BC. But it took for the Romans to arrive before winemaking was taken seriously. Exporting has been important to the Spanish wine industry from very early on. The higher alcohol content of the wines produced from the local varieties in the hot summers allowed the wines to travel well and during the 17th and 18th centuries they boomed due to Spain’s colonial holdings.

Interestingly Spanish bodegas were traditionally places where wine was aged as opposed to where wine was made. Even to this day the practice of buying grapes and wine is much more common in Spain than elsewhere in the world. It was this set up with allowed Spain to help Bordeaux over the centuries. In fact, Benicarlo (now known as Bobal) from Valencia was once an important ingredient in Claret, but it was Rioja and Navarra who were most involved with Bordeaux during the Phylloxera years causing the boom in the Spanish wine industry during the second half of the 19th century. It was these French winemakers who crossed the border who brought with them more advanced winemaking techniques, improving Spain’s wine quality especially in Rioja. In 1880 a rail link was completed to Bilbao from the village of Haro effectively making Haro the centre for shipping wine up to France.

However, this boom sadly didn’t last. In 1850 the first powdery mildew crossed the Pyrenees and Phylloxera followed a few decades later hitting the Eastern shores first but eventually reaching Rioja in 1901. The solution of grafting onto the Phylloxera resistant American rootstocks was well known, however, this was a costly and timely task and many of the French winemakers who had established themselves in Rioja returned to France. Those producers who remained replanted and dramatically changed the face of the vines grown as native varieties were replaced by international and more productive selections. For Rioja, the 1970 vintage returned the region to international attention and in other regions, such as Penedès, winemakers, notably Miguel Torres, began to introduce more scientific winemaking. The death of General Franco in 1975 and a return to democracy opened the economy and this, along with investment and increasing skills, lead to more consistent quality across the board from the huge volumes of bulk wine, right up to the icon wines which keep emerging across each region.

Grape Varieties

Whites

- Airén: Once the world’s most planted variety. Generally used for bulk entry level wines and for blending with Sauvignon Blanc. The wines are neutral and short lived. Also used for production of Brandy.

- Albariño: Primarily from Galicia it produces very aromatic wines with natural high acidity but silky in texture. It ripens early and has thick skins and lots of pips.

- Godello: Mostly grown in Galicia and produces creamy yet aromatic wines.

- Loureiro: A native Galician variety which adds perfumed aromas and acid to wines.

- Macabeo: The most common variety found in Cava with 35% of planting in the DO, also known as Viura in Rioja, it is a neutral variety well suited to traditional method sparkling wines.

- Malvasía: Originally from Greece, and generally used in blends.

- Moscatel: The ‘Grapey’ grape. Predominantly planted in Alicante and becoming popular in Navarra.

- Parellada: Best suited to higher altitudes, but often just plays a supporting role in the Cava blend.

- Treixadura: A slow ripening grape primarily planted in Ribeiro producing aromatic wines.

- Verdejo: Typical variety of the Ruedo DO, producing aromatic full-bodied wines which can handle oak. Often blended with Sauvignon blanc or Viura to add body. Historically used to produce sherry as it oxidises easily, to combat this, modern producers pack grapes during the cool nights.

- Xarel-lo: Often considered the top Cava variety it has natural high acidity meaning it often makes up most of the blend for longer aged Cavas. However, it is difficult to grow and performs best at lower altitudes. It’s early budding and late ripening giving it a long growing season. In youth it has fennel herbaceous notes that with long aging develop into honeyed warm pastry.

Reds

- Bobal: Mainly planted in Valencia and produces deep coloured full-bodied wines.

- Cariñena: Named after the town it originated from, the Do is now named after the variety as well. Old vine examples are high alcohol, high tannin, high acidity, bold and intense. (Carignan in France)

- Garnacha: this is a Spanish variety despite its association with the Rhône. Primarily planted in the Northeast regions (Rioja, Navarra, Aragón & Cataluña). Often blended to provide colour and fruit flavours to wines or used for Rosado production in Navarra due to its low tannins.

- Graciano: Grown primarily in Rioja and Navarra and blended with Tempranillo. Produces vibrant wines, with spicy notes, rich in colour with good acidity and tannin structure.

- Mencía: A very on trend variety planted mainly in Bierzo. Young wines are vibrant with red cherry and herbal notes, aged versions can have a deep brick red colour with complex peppery characters and meaty tannins.

- Monastrell: Typical in Murcia and south of Valencia. It has thick skins and is late to ripen, producing powerful structured wines with high alcohol. Difficult to grow, with Inconsistent yields year to year.

- Tempranillo: “Temprano” means early in Spanish, and the name Tempranillo relates to its early budding nature, although this does mean it is susceptible to spring frosts. Tempranillo is also known as Tinto Fino in Ribera del Duero, Cencibel in La Mancha and Ull de Llebre in Cataluña. It produces fresh and fruity young red wines, but it shows its best when oak aged. However, its thin skin also leaves it susceptible to rot.

Climate

Spain has a Mediterranean climate overall with cold winters and very hot summers. The sunshine is so relentless that often the vines shut down, effectively halting the ripening process, therefore long warm autumns are essential to ensure full ripeness is achieved. The major climatic challenge for the south, east and some of the northern regions is the summer drought. Dry soils cannot sustain dense planting, so in a lot of Spain you will notice that vines are planted unusually far apart, as a result Spain has more land planted under vine than any other country. They also favour low bush vines as another means of controlling vine vigour. Since 2003 irrigation has been legal to utilise in Spain, however this is only signed off on a case-by case basis, and generally a luxury only reserved for larger producers as they must bore for water and install large systems.

Winemaking

It is traditional in Spain to only release a wine when it is deemed ready to drink, allowing the wines to age in barrel and bottle for long lengths of time, sometimes too long… Originally the barrels used were American oak, used as it was easy and cheap to access thanks to the country’s transatlantic seafaring. However, in recent years, French barrels have become more popular amongst the new wave Spanish winemakers

The Regions of Spain

The Key Sub-regions of Spain

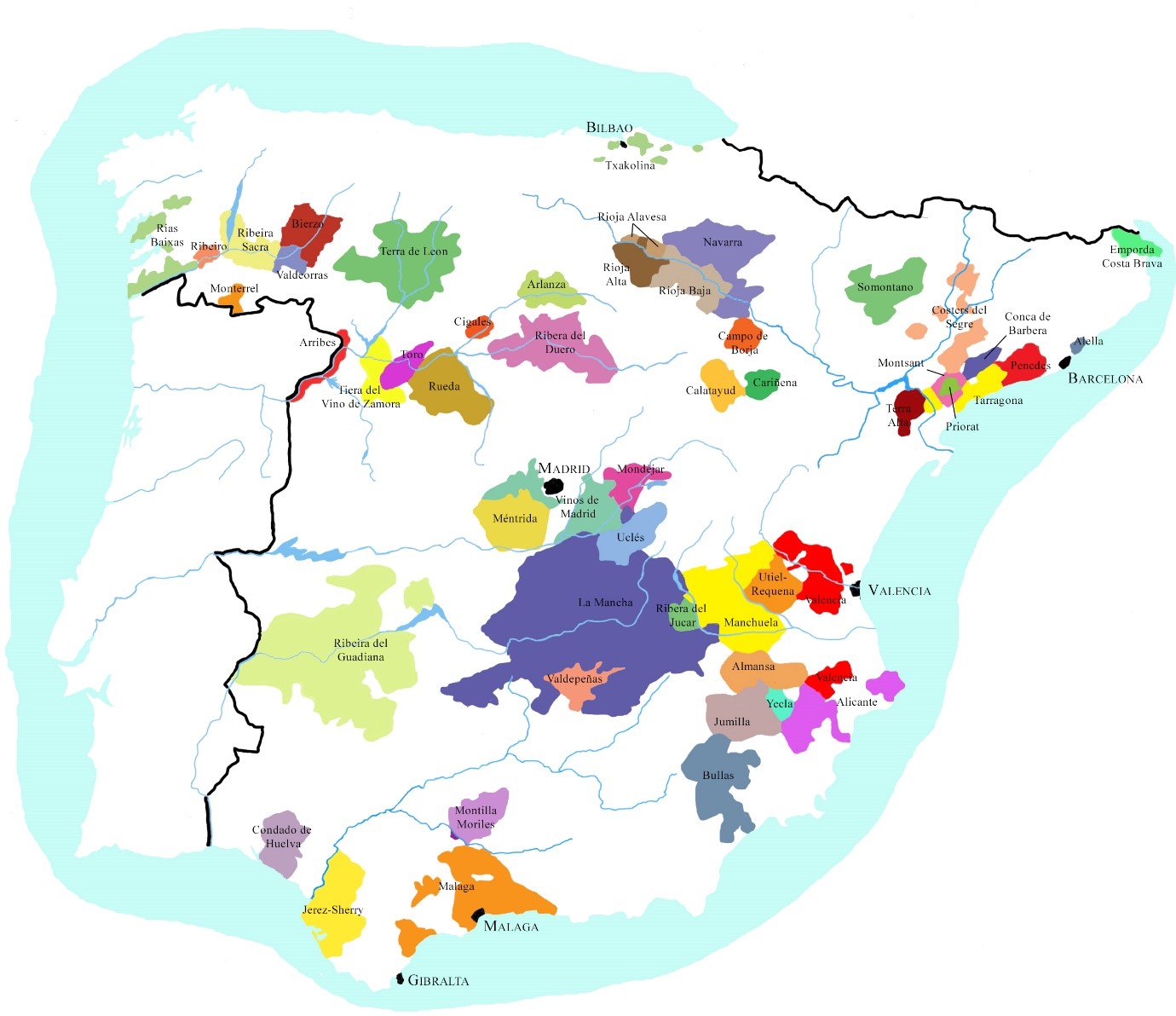

Like much of Europe Spain uses a DO system, however it is thankfully less complicated than France’s AC system. It was developed in 1932, with a couple of updates over the years to reflect the improved quality of wine being produced. There are now around 80 DO’s and 3 DOCa’s (Rioja, Priorat and Ribera del Duero). Each DO has a Consejo Regulador, a governing body that enforces the regulations of that specific DO. However, most of the DO’s are large and cover a myriad of terrains and conditions. This causes issues for producers where a DO specifies varieties or winemaking techniques that they do not think suits their specific terroir, and as such many producers work outside the DO as well as within it.

Galicia

This is the smallest and one of the wettest regions in Spain. The Atlantic, the hills, the wind and the rain are important geographic factors which influence the wine styles produced here. Indigenous varieties such as Albariño, Loureira, Godello, Treixadura and Mencía are in growth and exported wines tend to focus on the white wines. These have naturally high acidity and unlike much Spanish wine, do not need to be acidified.

- ías Baixas – Vines are typically trained on pergolas which help to provide ventilation, this is important due to sea mists which, even in summer, can affect vineyards. There are 5 sub regions of Rías Baixas all of which focus on Albariño, it is a thick-skinned grape so can resist the threat of mildew. Generally, wines are produced to be drunk in their youth, but more are experimenting with oak and blends for longer aged wines.

- Ribeiro – Planted mainly to Albariño, Treixadura & Loureira. Historically shipped wine to England long before the Douro Valley.

- Ribeiro Sacra – this sub-region is further inland and makes Galicia’s most interesting red, Mencía. It’s planted on impossibly steep terraces.

Castilla Y León

Castilla Y León is the heart of Spain and the largest region in Spain, and because of its location is one of the coldest areas in Spain, with long cold winters and short but ferociously hot summers. Most vineyards in this huge region lie in the high, landlocked Duero Valley.

- Toro – In 1998 there were only 2 bodegas but by 2006 there were over 40! The demand for these rustic full-bodied reds made from its local strain of Tempranillo, Tinto de Toro, has skyrocketed. But the notoriety of this region went into overdrive when Vega Sicilia established their Pintia Bodega here. Tinto de Toro accounts for 80% of plantings with vineyard altitude ranging from 600-750m on red clay and sandy soils. Most of the wine is aged in oak for a minimum of 12 months, producing deep crimson, robust and seriously fruity wines.

- Ribera del Duero – This DO was created in 1982 with only 24 bodegas and by the end of 2005 there were over 215. Although barely known in the 1980s, Ribera del Duero has stormed onto the global wine scene to rival Rioja. Centred around the Duero river it has a continental climate and its altitude of 850m means that nights are remarkedly cool. Spring frosts are a common issue and grapes can still be picked into late October. However, thanks to cool nights, wines tend to retain acid and can be very concentrated with intense colour and fruit flavours all thanks to the longer growing season. Vega Sicilia was one of the first to see the potential of the region when they planted vineyards in the 1860s focusing on Tempranillo and Bordeaux varieties (due to the influence of Bordeaux merchants in nearby Rioja). Their icon wine, Unico (a blend of Tempranillo and Bordeaux varieties), is only produced in the best years and is aged longer in oak than nearly any other table wine, generally being released after 10 years. However, it is the local Tempranillo (Tinto Fino or Tinto del País) that rules in this region, with only a small amount of Bordeaux varieties planted and a little Garnacha. It has extremely varied soils, creating uneven ripening within single vineyards, although to the North of the Duero the Limestone outcrops help to retain the little rainfall. Spain’s most expensive and rarest wine, Dominio de Pingus, is also produced from grapes grown in this region, although the producer closely guards their grape sources, but inevitably the most coveted are those with the oldest most gnarled low Tinto Fino bushes.

- Rueda – The most famous white wines are made in this region using the local variety, Verdejo. Sauvignon Blanc has also been planted more recently. The reds tend to be Tempranillo and Cabernet Sauvignon. Winemakers can use Vino de la Tierra Castilla y León designation to use other varieties.

- Bierzo – In the far north-east of the province and with similar rainfall to Gallicia, Bierzo is most famous for reds from Mencia, which can vary from crunchy red fruits to oak aged and dense as Reservas and whites from the appley Godello. Although more expensive than they were, they still represent good value.

Rioja

As previously discussed, Rioja entered the international wine market when the Bordeaux merchants came looking to fill their tanks when Phylloxera hit north of the Pyrenees. They had already heard of the potential of Rioja thanks to Marqués de Riscal and Marqués de Murrieta setting up bodegas just east of Logroño in 1860 and 1872. It was the Bordeaux merchants who introduced aging wines in small barrels, and due to its transport links Haro became the centre for these merchants to set up new bodegas. Until the 1970s, Rioja was primarily made in juicy styles, fermented fast and then aged for many years in American oak, resulting in pale wines with vanilla sweetness. However, in recent years control of quality has improved with most bodegas making their own wines and owning their own vineyards. Today, Tempranillo enjoys a much longer maceration and fermentation before aging in oak for a shorter length of time before being allowed to age in bottle. It was Marqués de Cáceres who introduced new French oak in 1970 and now French oak is often used over the sweeter American options. The result are wines which are deeper and fruitier – often referred to as a modern Rioja. Western Riojas tend to have more acidity and tannins, while those to the east have less. White wine production is small, with only a 7th of vines dedicated to the white varieties of Viura and small amounts of Malvasía and Garnacha Blanca. Most commonly produced are young easy drinking styles, but oak-aged white Rioja is one of the great white wines of the world, such as López de Heredia’s Tondonia.

Rioja experiences the climate problems of a marginal region, although the Sierra de Cantabria does protect Rioja from the Atlantic winds, in the far northwest of the region some of the highest vineyards above Labastida struggle to ripen. However, in the east, vines easily ripen at altitudes of 800m thanks to the warming influence of the Mediterranean. In fact, growers in the east may harvest up to 4 – 6 weeks before those based in Haro. The region is divided into 3 zones;

- Rioja Alta – this is the western higher area south of the River ebro. Clay is the dominant soil type on the river terraces.

- Rioja Alavesa – in the Alvava province (basque country) and may as well be another country with its own language, police force and grants which has enabled more bodegas to invest in the northern side of the Ebro. Limestone is the dominant soil type on the river terraces.

- Rioja Oriental (formerly Rioja Baja) – this is the hotter eastern section of the region, sometimes (incorrectly) considered to be inferior. The soils are even more varied than those in Rioja Alta, and vines are more sparsely cultivated. In the western areas, low bush vines are planted on soft red clay or limestone tinted yellow by alluvial deposits. These terraces have been eroded by the river, with the higher sites being the best.

Tempranillo is most important variety followed by Garnacha which are often blended together. It fairs best in Rioja Alta upstream of Nájera and in Rioja Baja in the high vineyards of Tudelilla. Small amounts of Graciano are planted in Rioja, and Mazuela (Carignan). There is some experimentation with Cabernet Sauvignon which is allowed, although it’s barely tolerated.

Navarra

In the 20th Century Navarra was planted primarily to Garnacha and produced dark coloured Rosados and strong deep bulk reds. However, more recently, an influx of plantings of Cabernet, Merlot, Tempranillo and Chardonnay have threatened Garnacha and now Tempranillo has overtaken Garnacha plantings. Co-operatives still produce a lot of generic Garnacha, though premium producers such as Chivite recognise that old vines of this varietal have their place. Interestingly Chivite has withdrawn from the DO as they do not believe in the restrictions it enforces, particularly when it comes to Rosado production. In Navarra DO a Rosado must be dark in colour, however Chivite, seeing the popularity of pale Provence style Rosés have produced their own pale Rosado (in collaboration with 3* Arzak restaurant). There are 5 subzones of Navarra covering a vast array of topography, from the southern hot, dry & flat Ribera Baja and Ribera Alta lying on the banks of the Ebro, which must use irrigation, to the northern areas which are less planted and cooler.

Valencia

Covering Spain’s central Mediterranean coast, Valencia has experienced rapid progress in terms of improving quality as previously it was regarded only good enough to produce bulk wine. Producers are now investing in producing decent wines with most indigenous varieties being blended with international. Regions included in this area are Manchuela, a high plateau with limestone deposits which focuses on Bobal, Utiel-Requena, also focusing on Bobal with vineyards at 600m above sea level. Also Almansa, Yecla, Jumilla, famous for its Monastrell and Alicante.

Somontano

Somontano translates into “at the foot of the mountains”, which is apt given on a clear day you can see the snow-capped Pyranees in the distance. However, it is the Sierra de Guara and the Sierra de Salinas mountains which make viticulture viable in this area as they provide protection from the cold northern influence. This protection coupled with the gentle south-facing slopes for the vineyard sites that is. The local government petitioned for DO status in the 1980s encouraging producers to plant Tempranillo and international varieties to compliment the local Moristel and Parraleta vines. While still not as renowned as its neighbours, Somontano is a great source for reliable and great value wines. The wines are generous but not overpowering, thanks to the sandy soil, with zippy acidity as its distinguishing marker.

Catalunya

Stretching from the hot Mediterranean coast to the high altitudes of the Serralada mountain ranges. They produce a wider range of wine styles here than any other region in Spain, from the crisp Cava to the syrupy sweets. However, it is Cava which this region is best known for, and 95% of all Cava is produced here, centred around the fertile plateau of the Penedès area. Cava is dominated by two producers – Cordoníu and Freixenet. The process is the same as champagne, utilising traditional methods, however the grape varieties used are different. The traditional and local varieties are Macabeo which provides the bulk of Cava plantings due to its late budding protecting against Penedès spring frosts, Xarel-lo is considered the finest traditional variety and Parellada can provide crisp apple characters if not over-produced. However, recently, Chardonnay and Pinot have been included in the DO, the latter used for the increasingly popular Pink Cava. Huge steps have been made in the quality of Cava through lower yields and extended bottle aging. It was also the Catalans who invented the Gyropalette providing a more efficient and cost-effective process than traditional hand riddling.

- Priorat – Before the arrival of Phylloxera there were 5,000Ha of vines planted in Priorat, but by the time René Barbier arrived in 1979 there were only 600Ha of mainly Cariñena left. The scarcity of these wines helped them reach international acclaim, and a sudden influx in investment means there are now over 70 Bodegas here. So, what makes the wine so special aside from its scarcity? The soil. It is an unusual licorella – a dark brown slate sparkled with quartzite which provides Priorat with its defining mineral characters. These soils are unusually cool and damp which means they don’t need to irrigate here despite only receiving 400mm of rain on average/year. This means that in the best sites the yields are super small producing concentrated wines. Cariñena is still the most widely planted but only the oldest vines produce any wine of quality. Nowadays it is the older Garnacha planted in cooler, slower-ripening sites which provide the backbone of most serious Priorat.

- Penedes – For still wines of the region Penedès is the leading DO utilising international varieties more than anywhere else in Spain, thanks to pioneers such as Miguel Torres planting Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay in the 1960s. The hottest, lowest vineyards of Baix-Penedès by the coast grow Moscatel and Malvasía grapes for dessert wines. At medium altitudes Cava dominates, and higher up (800m) growers are working hard carving vineyards out of the Mediterranean scrub to plant low-yielding indigenous and international varieties.

- Montsant – Once part of Tarragona, the higher western vineyards established their own DO in 2001, encircling the Priorat DOCa. They produce concentrated dry reds from a wide range of varieties, differing from Priorat due to the soil.

- Tarragona – Immediately west of Penedès, supplies grapes for Cava production and also still produces its traditional sweet and heavy red wines in the eastern coastal plain. They are long aged in barrel and often take on a Rancio character.

Castilla La Mancha Most central of all to Spanish life is the Meseta – the high plateau south of Madrid covered in endless flat vineyards. The chief DO is La Mancha, although DO vineyards account for less than half of all plantings in this area. However these still cover more ground than all of Australia’s vineyards put together. Like most of Spain a radical change has taken place, with producers moving from light to dark skinned grapes in the 1990s and by 2005 more than two thirds of all wine made in this region were red. Garnacha and Tempranillo are still grown here, but Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah have taken dominance. Due to its super warm climate picking generally begins in mid-August.

Market

Previously Spain was a great wine consuming country, however, since the 1970s, the domestic market has been in decline. In fact, Spain’s per capita wine consumption is much lower than in the UK, I don’t know if I’m really all that surprised by this. However, remember that Spain has a huge Tourism industry, which we are top contributors to, so adding more than 70 million tourists that are included in this statistic, Spain’s consumption is significantly lower than the UK. Thus, Spain is a huge wine exporter comparable to Chile and Australia. More than two thirds of Spanish production, around 24 million hectolitres leave the country every year. Therefore, the whole production system is steered towards exports, at all price levels. As previously discussed, Spain is cheap, almost half the wine production is sold at unbeatably low prices (in an average vintage). No other country can compete with Spain in terms of price to quality ratio. It is this over deliverance on quality at all price points that have led to an increase in export of more premium wines, although the value of Spain’s annual wine production, around €4.8 billion, is still far away from France’s or Italy’s. Still red wines account for €2.7 billion in value, followed by still white wines at €1.1 billion. Although volume for DO wines is low at 1.3 billion litres, the value is more than double the value of bulk wines.

Barbaresco and Barolo Vintages

2008: Very good quality for Rioja, however cooler weather in Ribera del Duero, resulted in elegant wines.

2009: Very hot conditions but well-timed rains in Rioja and Ribera del Duero rescued the vintage.

2010: Another top year, but Top year for Ribera del Duero as promising as 2004 with good quality in Rioja as well, better than 2009.

2011: Hot in Rioja and Ribera del Duero producing powerful wines which may have lower acidity particularly in Rioja.

2012: Another small vintage due to dryness means that Rioja wines are concentrated with high tannins.

2013: Very good year, at the time much heralded but some were a bit dilute and not all have aged gracefully.

2014: An improvement on 2013 in Rioja, but still some issues with grey rot.

2015: Hot and dry in Ribera creating wines full of flavour with soft tannins and high alcohol. Alcohol also higher in Rioja but with high quality levels all round.

2016: Unlike Catalunya, Rioja had a large vintage, largest since 2005. Excellent, quality with modest alcohol.

2017: A super tough year with the frost and drought reducing yields by minimum 25%. Wines have higher than average alcohol, tannin and extraction.

2018: Both Rioja & Ribera del Duero have lower than average alcohol levels, and higher than average yields.